You should probably find a new best friend

Who lives where you live

$100,000 friends

Recently over dinner with new friends I asked, “How much would you pay to have your best friend live on your street? Wherever you move poof they’re your neighbor and they’ll never know you paid.” After a moment of thought, the couple independently arrived at the same number: $100,000 each.

By this point in the conversation I knew that they had normal enough jobs, and it was reasonably safe to assume their combined after-tax income was also right around $100,000. I did some back of the napkin math and it turns out what they were suggesting was: “Outside of basic sustenance we’d pay every single dollar each of us makes for doing 16,000 total hours worth of work over the next four years to have our two best friends live within walking distance.”1

Were they just bad at theoretical scenarios? Were they insane? I tried to find out. Over the next several months, I asked the same question to fifty people. About thirty of them said $100,000. Ten of them offered more. Two said $1 million. Three said, “50% of my net worth.”

Before I began asking others this question, I’d asked myself, and the number I wrote down in my journal was: $100,000. Below it, “Ideally in installments. I’d pay more if I could.” This turned out to be the going rate, but really it was symbolic. Shorthand for an uncomfortably high, round number, meant to flirt with the absurd and clearly suggest: a lot, like a lot.

The question also animated people with excitement. It typically led to wild stories, cherished qualities, and qualifying explanations about the particular greatness of certain best friends. It’s the kind of thought experiment that makes you feel things, but unfortunately it remains theoretical. There’s usually a legitimate reason why we can’t move, or they can’t move. Sometimes it’s work, sometimes it’s family. Some people have multiple best friends from different stages of life in different cities. There are innumerable plausible reasons, and sometimes they’re not specific. A word I heard a lot was: “impossible.”

Indeed, it may be impossible or impractical, but as soon as you’ve asked yourself this theoretical question, priced things out, and eyeballed an eye-watering number—there are two things you can and should do. First: you should plan a non-negotiable recurring trip with the best friend(s) you have in mind. And second: you should take dramatic action to find more people like them where you currently live. In other words: you should find new best friends locally. Not normal friends, best friends.

I won’t explain how to plan a trip with your current best friends, I’ll only reiterate that you should and that it should be a regular thing. There is no substitute for weekly in-person contact with your closest friends, but the next best thing you can do is invest in semi-regular experiences together. Even at great expense or inconvenience.

The question of finding new best friends at a new stage of life in a new place is more fraught and controversial. Is it even possible? I think so. For starters, it helps to consider what answers like “$100,000” reveal about the nature of friendship.

The power law of friendship

The answers to my theoretical question revealed an under-appreciated consensus: there’s a power law to friendship, and the rare-air of best friendship is worth more than all the others combined. If you’ve lived a chapter of life alongside your best friend, then you know that there’s nothing that makes you feel more alive or more yourself than highly regular time spent doing things together. Nothing creates more Technicolor memories per unit of time. Nothing compares to the rhythm of life, to the belly laughs, to the depth, to the love, to the mischief, to the mutual understanding, to the feeling of being understood across multiple contexts. Aside from a romantic life partner, it’s incomparable. At peak moments, during peak memories, it feels like the whole point of life itself.

With this in mind, the same reflexive logic unfolds in everyone who is pressed to put a price on living near their best friend. They confront the value of friendship in monetary terms, they understand that money buys things, and they simply can’t think of anything remotely close to the value of a best friend.2

So they say “$100,000” with a straight face. And the number typically increases when you press them.3

Money is time

Everyone recognizes the value of a best friend emotionally, and most people are capable of putting a kind of price on it theoretically, but the crucial missing link between a theoretical thought experiment and a galvanizing wake up call is the translation of money into time. Since “$100,000” is just another way of saying: “I’d pay a lot of a thing I traded a bunch of my time for in the past”—an equal substitute would be to carve out an equivalent amount of future time, and spend it searching for a new best friend nearby. Could you find a best friend if you were fully committed to the problem and you gave yourself 1,000 hours to solve it? That’s roughly five hours per week of friend-finding-effort for the next four years.4 Feels like a slam dunk to me.

But this is where my thought experiment runs into the most pushback. Most people don’t believe they could proactively go out and find a new best friend for two reasons: first, they believe there is an irreplaceable ‘specialness’ to best friendship that derives from shared life experiences during formative stages of life; and second, they believe it’s hardly even possible to go out and proactively find okay friends, let alone a new best friend.

To the first point, it may be a bit late to make this semantic concession, but I don’t believe in best friendship as a singular title (given only to one person), I believe in it as a friendship tier. It’s the highest bar. I have plenty of friends, but only four people in this tier. I met each of them at different stages of life—some in my childhood, some relatively recently.

One of my best friends, Tim, skyrocketed into the top tier within a matter of weeks, and solidified a permanent place in the category over the course of a year. He is my counterpoint to the idea that best-friendship can’t happen in a new chapter of life, or that it can’t happen quickly. It simply took two people recognizing how much potential there was in the relationship (something that is usually easy to recognize), and going all in. Tim and I spent a ton of time together over the course of a year, but that’s really all it took—densely experiential-time piled on top of extremely high compatibility. You can’t replicate an old friend’s distinct flavor of specialness or a shared history, but you can develop something equally valuable over time with new people in new chapters, which reflect the ways you’ve changed.

To the second point: how do you meet a Tim? This can’t be planned. And this is what people hate. The way Tim came into my life was totally ridiculous: he met my brother lobster diving. But there is a difference between predicting how something very specific will happen, and radically increasing your odds of orchestrating a desired outcome. The way to manifest new, best-friend-caliber relationships is exactly how you solve any big, nebulous problem: you spend a lot of time on it, you design a good plan, you continuously pivot and refine your plan through trial and error, and you don’t stop until you’ve solved your problem. If you spent 1,000 hours looking in earnest for your next Tim, you’d find one.

You’d even find one without employing especially creative solutions—by simply: joining a few clubs, attending interesting events, volunteering somewhere, becoming a regular. Socializing a lot. Saying ‘yes and’ a lot. Accepting and extending invitations. Asking new people to introduce you to their most interesting friends who share your niche interests. It’s not complicated. You simply must be willing to stay at it, even if it takes five hours per week for four years.

Rejection and awkwardness, a small price to pay

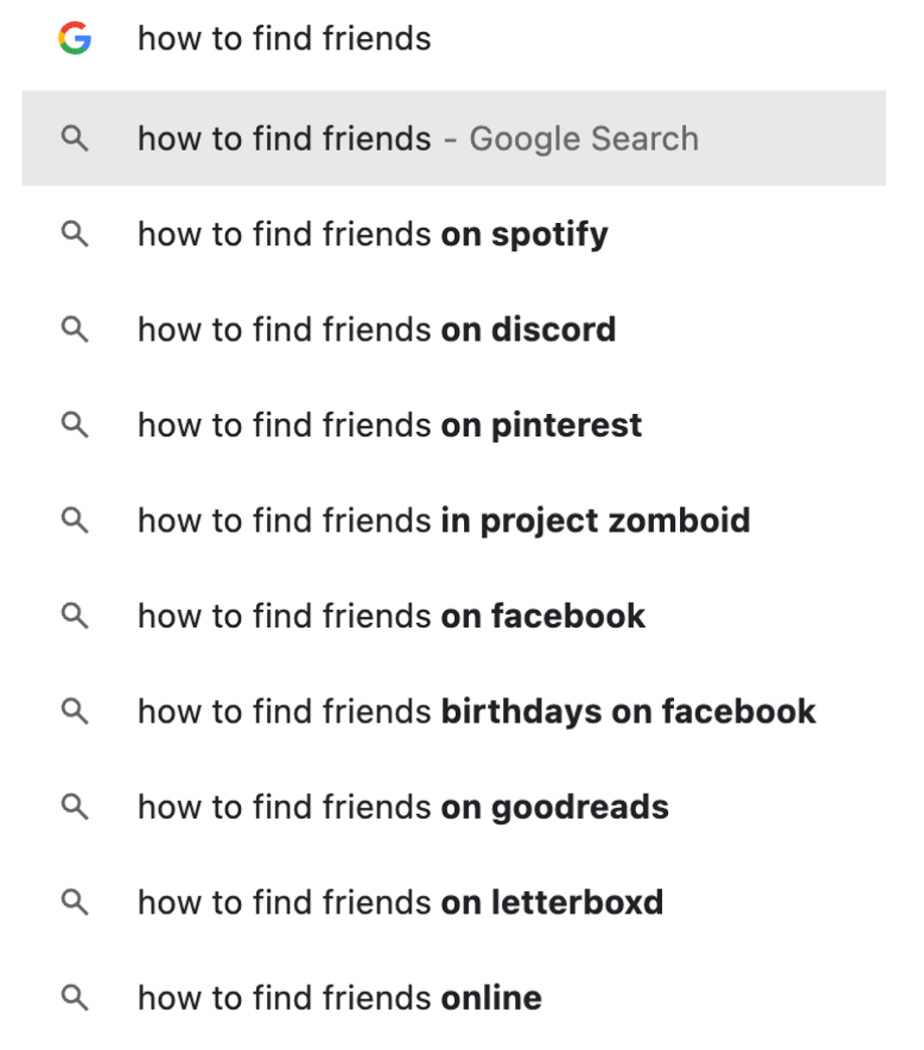

People shudder at friend-finding in general. It’s one of those open-ended problems that even intelligent and highly capable people are selectively agentic about: they complain about how hard it is, without directing legitimate effort or creativity at the problem.5 In reality, the cultural and individual resistance (and the acceptance of loneliness as an alternative) is mostly related to fear of rejection and aversion to awkwardness. It also has a lot to do with avoidance of personal responsibility—without the possibility-rich social environments of our youth (school, team sports, camps, etc.), adults are forced to take responsibility for creating the conditions that will get them what they say they want. And it’s true: there is no ready-made playbook for finding friends, no easy button, no dependable, swipe-able app. Good luck Googling it.

But is it impossible? Of course it isn’t. People have best friends, and they make new ones at all stages of life. The problem is that it’s not pursued as a solvable problem, commensurate with the huge value we place on it, or with the amount of effort and time required to make it inevitable. It’s approached as a thing that happens to you if you’re lucky—not something that you can happen to by making your own luck.

Baked into my original question is an assumption about modern friendship that proved to be categorically true: nobody lives in the same place as their best friends anymore. I never had to qualify the question. People just understood that the premise depended on their best friends living somewhere else, and in basically every case this was true.

So chances are, your best friend lives far away too. If that’s the case, my follow up questions for you are the same non-theoretical ones I found myself asking people who said “$100,000”: What are you doing to make a new best friend where you live now? How much time is the problem worth to you? Do you think you could find a new best friend if you spent 500 hours working hard on it? 1,000 hours? 10,000 hours? Even more?

Wouldn’t it be worth it if you could? What is a better use of time?

If you enjoyed this essay, please click the little heart below (or share it). It’ll help others find it.

Thanks to Michael Dean for feedback on this piece.

I remember exactly what I thought when I ran the numbers: a Rivian R1T is $80,000—and I really wanted one. Then I thought, which would make me happier: an electric truck or daily interactions with my best friend? The answer was so obvious that the question felt insulting. I could think of nothing at any price that made the question more palatable.

Given the option in reality, I think many people would actually pay an even larger number—a figure approaching the word “priceless.” In response to my question, several people gave a “whatever it takes” type of answer at first. Many suggested a high-percentage of their net-worth. The percentage-of-net-worth answer was actually the second most common genre of answer, and it was the response given by the people who thought about the question the longest. In every case, the number was proportional to the means of the person answering.

If you value your time at $100/hour, this is $100,000 worth of your time.

Cate Hall’s brilliant piece about “Maybe you’re not Actually Trying”—points out that the same types of people who are developing artificial general intelligence at the office, go home after work and play video games alone because they’re resigned to the impossibility of making IRL friends. In reality, they’re not actually trying in any way that resembles the effort they apply to other areas of their life.

I’ve been wrestling with whether to move to a city where a bunch of my friends live, this just put me over the edge!

Another platinum essay. As I continue to go all-in on one book (the 6 pillars of Self Esteem) at your suggestion, I find it easier and easier to have random conversations with people. I think that will serve me well as I go in search of a propinquitous best friend with intentionality. I was already thinking about looking for more friends nearby, but you brought two major insights: first, the idea that a best friend is possible in my immediate area; and second, that I should be devoting the same time and effort as I would to making my next $100,000. That means deleting some low-value activities without mercy, and I think I know exactly which ones to delete. Thank you!