The other day, I arrived at my co-working studio and found that my favorite desk was taken. The perpetrator had left behind a collection of personal belongings, and as I scanned the desk my attention stopped on something left behind: a cell phone, abandoned and impotent, imprisoned inside of a clear, acrylic lockbox with a countdown timer. I recognized the box at once: the KSafe, “America’s #1 Habit Breaker.”

I knew all about the KSafe because there isn’t a focus-related quick fix between Bend, Oregon and Bangladesh that I haven’t used or contemplated using, and I also knew that this person was dealing with a habit that a lockbox had no business promising it could break.

Though mostly futile, these kinds of focus Band-Aids make good business and they’re the solution most commonly deployed upon our wandering attention. Stop-gap solutions like: Red Bull, AdBlock, Forest, Freedom, Self Control, Focusmate, nootropics, lion’s mane, Brain.fm, Instapaper, Mailman, Screen Time, greyscale, etc. etc. et. al. If I listed them all, I’d break the Substack word count limit. Focus aids can be helpful when they play a support role in your effort to concentrate, but even with an entire bandolier at your disposal, you’re still walking into a wildfire with a water pistol.

You can blast your brain with stimulants and hide from your phone all day long, but you can’t hide from yourself. You can’t hide from your mind. And the mind is where your attention breaks down, or doesn’t. So you need to learn a few things about how it works, and then you need to train it to work more effectively.

About four months ago, I was the kind of person who might resort to Ksafe Matryoshka: placing my phone inside of one Ksafe before nesting it into another one, then into another Ksafe, and so on. My attention span had tumbled to its nadir and I was willing to try anything.

So I did try anything, and everything. And after much trial and error, I became the type of person you have to hover above and repeat the name of three times to arouse from an intense and singular attentiveness. I became undistractable. The first big unlock for me was when I learned how attention actually works.

Previously, I thought about attention as getting “locked in” or “being in the zone.” I thought it was one thing. It turns out that it’s something more like three things, three cognitive-clusters—like a three-parted network within the brain, where each part performs a distinct and familiar function. The names of these clusters are the:

Orienting system aka flashlight

Prioritizing system aka prioritizer

Alerting system aka lighthouse

The orienting system is pretty close to what I used to imagine attention was entirely about; it refers to the tunneling type of concentration that we associate with being “locked in” on something. Think of this system as your flashlight. When you point your flashlight at something, you create a beam of light, and that narrow circumference of light is surrounded by an infinite expanse of dark. The light stuff is the field of view in your mind’s eye, it’s what you’re focused on; the dark stuff is everything else that you no longer notice.

You have a limited amount of attentional space, and when you’re super focused on something your flashlight uses up all of that space. Your flashlight can be directed inwardly (e.g. reflection, rumination, imagination) as well as outwardly (e.g. a book, a TikTok video, your dog); and it can bend time: you can shine it on the thing before you in the present moment, you can shine it into a memory of the past, and you can shine it imaginatively onto the future.

If you have perfect powers of concentration, you can shine your flashlight exactly where you want, exactly when you want, and you can hold it there until your higher self says: “Times up! Great work reading Infinite Jest for 30 minutes without thinking about anything else. We’re done here.” Then you move on to the next most important thing, and you shine your flashlight on that next thing.

Unfortunately, you don’t have perfect powers of concentration. Your flashlight operates on some continuum of unreliability, because your higher self has been utterly annihilated by things like sugar and modern technology and anomie. Year by year, your higher self is atrophying: instead of holding steady on that one thing you decided you wanted to focus on, it is relentlessly jerked around throughout the day by notifications, distractions, undefined priorities, inner urges, interruptions, and more. The average length of time that a person now holds his/her attention in one place is 47 seconds.1

This so-called higher self is calling very important shots, and it keeps getting hornswoggled into trivial matters—but, what exactly is it? You can think of the higher self as a triage machine in your brain’s prefrontal cortex. Attention researchers call it the central executive, essentially your brain’s CEO, but this is oddly inconsistent with the rest of their vocabulary so we’re going to call it the prioritizing system, for short: the prioritizer. Your prioritizer is the attentional brain within your brain, it’s the traffic controller that facilitates handoffs of attention. It decides what to point the flashlight at based on your goals, safety, desires, urges, etc. If you don’t have a clearly defined priority and a clearly structured set of boundaries, your prioritizer will be forced to negotiate between a pluralization of competing options, pretty much all the time—every red-bubble, ding, urge, and inner impulse presenting yet another option to consider.

We’re not done with the prioritizer yet, but before we go any further it’s important to understand the role of the last system of attention: your alerting system. Your alerting system is linked to your survival instinct. It has been fine-tuned over the centuries to anticipate and react to environmental threats, and it’s easiest to think of it like a lighthouse—as your diffusive attentional awareness. Your lighthouse scans the periphery broadly, focusing on everything generally, and focusing on nothing specifically. This is the part of your attentional system that picks up background noise and passes it along to the prioritizer, which must then decide whether that information is worthy of redirecting your attentional flashlight towards and taking a closer look at. If you’re in a super stimulating environment like an airport, your alerting system is going to be absorbing all sorts of colorful and potentially important information—beeps, buzzes, juicy eavesdropping fodder, awkward families doing awkward things, the creepy guy next to you in a Slipknot shirt with wired headphones watching YouTube Shorts on his phone and loudly slurping a Mountain Dew, flight attendants apologizing or not apologizing about delays and saying names and flight numbers into a PA system—your lighthouse picks up all of this stimuli (and so much more) and passes it along to your prioritizer for processing, while you’re sitting there trying to point your flashlight at a book. Here are some ways this could play out:

Bad: Your lighthouse dutifully shares all these stimuli with your prioritizer, and your prioritizer is dysfunctional and basically useless and it yanks your flashlight around the airport towards all of it. Towards everything except the book in your lap. Increasingly towards the Mountain Dew guy. You sit there ‘reading’ for 45 minutes without flipping a page. You start and stop the same sentences and paragraphs. You feel scattered. Eventually people around you stand up and form a line, and you join them. You board your flight.

Good-ish: You’re wearing Bose 700’s and listening to brown noise on full volume and facing the tarmac and your book is really interesting and you’re fully absorbed by it. Your lighthouse is essentially shut out from environmental stimuli. Your prioritizer keeps your flashlight pointed at your book. After a long while, you feel a sudden inner prompting. Something is wrong. Your flashlight searches inwardly for more information and context. You remember you’re in an airport(!) and you look up and realize everyone has boarded your flight. You gather your things and race to the airbridge entrance and just barely make it onto the plane.

Elite: Your lighthouse picks up and transmits all of the insane airport stimuli over to your prioritizer. Your prioritizer is super functional: it filters between noise and signal, and keeps your flashlight pointed at your book, until the PA announces a boarding call for your flight. You calmly put your book in your bag and board your flight.

The prioritizer is the entire ballgame when it comes to your attention. Your attentional strength and endurance depend on it. Whereas your alerting and orienting systems have their jobs—to absorb and be absorbed by stimuli—and they’re going to mechanistically go about their jobs whether you like it or not, your prioritizer can suck at its job. It can let you down. It can lose its grip. It can be confused by your inner turmoil and bamboozled by your environment.

Your prioritizer can prioritize the wrong things, but it can also be trained, strengthened, protected, and supported—to the point where it can become the most valuable tool in your entire biological toolkit. Just imagine, for a second, having a super well-trained prioritizer which points your flashlight of attention on whatever you want, for as long as you want, while filtering out irrelevant background noise and alerting you when something genuinely important comes up. This is unheard of nowadays, but it is possible with enough training, support, and structure. When I say that I’ve gone from super distractible to a black belt in the art of attention, what has happened from a neurological standpoint is that my prioritizer has reached Herculean fitness levels. Everyday, before the day begins, my prioritizer knows the plan, and everyday it sticks to the plan. I will teach you how I did this. No Ksafe required. The roadmap is below.

The Triangle of Attention

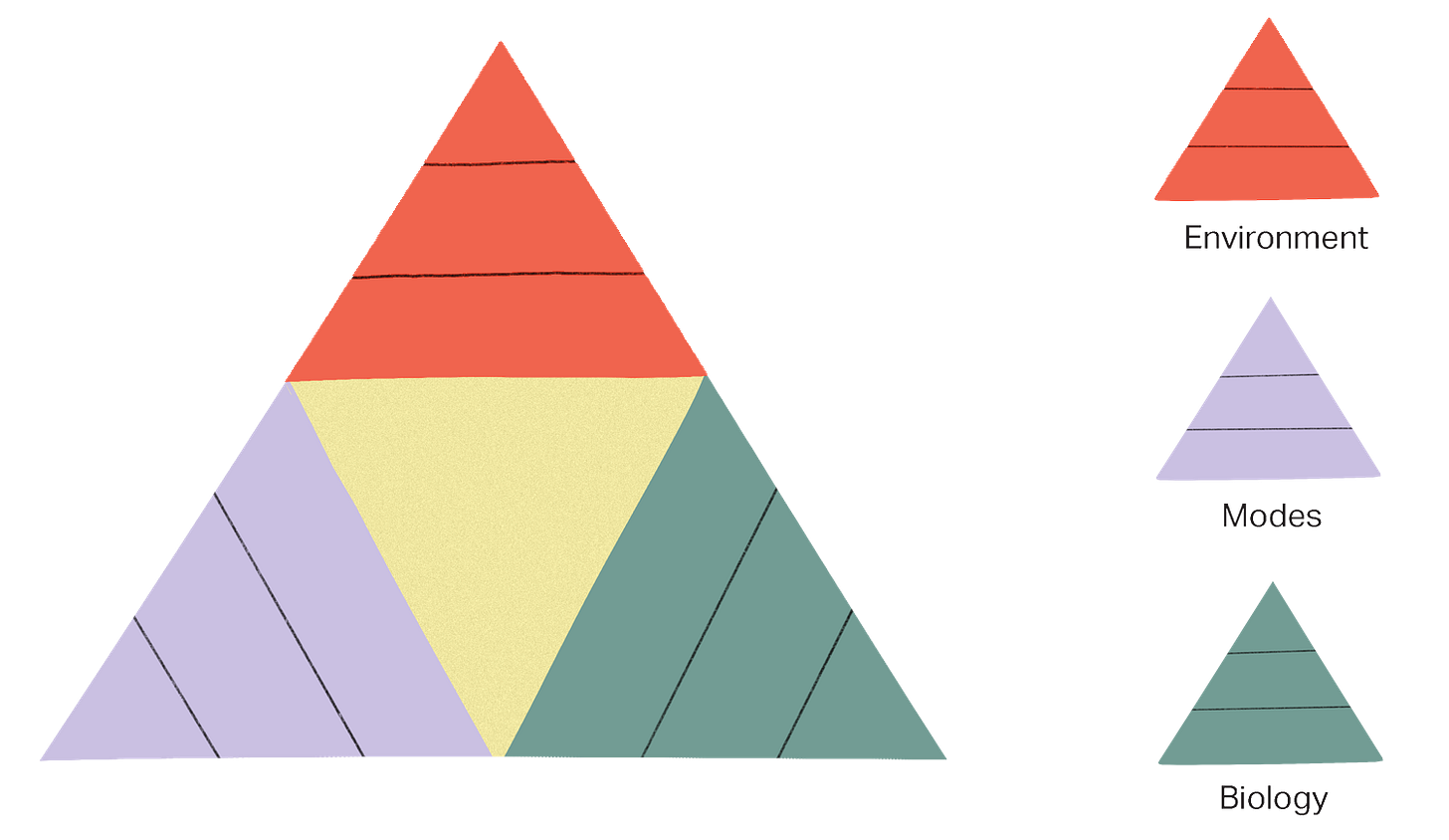

On the path to restoring your prioritizer there are nine steps, and it’s best to ascend them in order. When all of the steps are complete and integrated, they come together to form a tripartite triangle. Failure at any level within the triangle will compromise and rapidly fatigue your attention, but they can be effortlessly managed and healthily maintained through habits, practices, and routines. The nine parts are grouped into three stages: environment, modes, and biology; which each break down into three separate steps. I will walk you through each stage and step. Here is how you can visualize them, as well as a preview of what each step entails.

Stage 1: Environment of Distraction

I’ll start off by sharing the software, systems, and tools that I’ve found most effective for managing phone, desktop, email, messengers, and more. And we’ll develop a plan for media consumption: news, social media, information, content, etc.

Dimming the Lighthouse: managing unwanted stimuli, limiting unnecessary stress, and quieting rumination

Supporting the Prioritizer: preventing impulses and bucketing priorities

Intensifying the Flashlight: chemically enhancing wakefulness and readiness

Stage 2: Modes of Focus

We’ll explore the three fundamental building blocks for improving your focus, and the progressive order in which you should understand and implement them.

Monofocus: unraveling the myth of multitasking, and exploring alternatives

Unfocus: taking breaks to create a canvas for neural recovery and dot-connecting

Metafocus: reducing the latency of self-awareness through mindfulness meditation

Stage 3: Biology of Attention

Physiologically priming your body for focus. Science but hardly rocket science.

Fuel: the astonishing interplay between nutrition and concentration

Sleep: the imperative battery charging process for neural restoration, focus capacity, and endurance

Flow: the importance of swimming downstream; and finding the intersection of challenge, skill, and purpose

Advanced Attention

Once you have a functioning prioritizer, you’ll be ready for Advanced Attention. These are the deep-cut, lesser known drills, practices, and behavioral changes that will allow you to improve your concentration beyond your wildest dreams.

Pre-Prioritizing: structuring the day to aid your prioritizer and protect your circle of attention

Resonance Frequency: using biofeedback to create a trigger for clarity, calm, and recovery

Pacts, Pledges, Accountability: leveraging the psychology of consistency and commitment

Believe It, Become It: reinforcing and living into a constructive self-image

Soft Zone Training: concentrating while the roof is falling in

Extras: Training, Practice, More

At the end (if there is interest), I’ll try to supplement the core lessons with short, actionable posts to support your progress in different ways: through challenges, drills, experiments, and by addressing specific situations.

Attention @ Work - how to structure your time and manage interruptions when you’re not in complete control

Training Plan: After I finish explaining everything above, I will share a prescriptive, structured 10-week program that integrates everything above so that you can see how it call comes together (drawing from the program I used to restore my attention)

Practice Drills and Experiments: Like any other skill, concentration is something that can be practiced deliberately. Some drills will be in the 10-week training program, but there are plenty of additional supplementary exercises that you may want to try.

Mailbag: Along the way, if and when questions arise, I will round them up and answer them in FAQ posts

That’s the roadmap. Some of it is right out of the concentration textbook, and some of it is thirty hyperlinks removed from the mainstream world of attention. I’ll try to make everything more practical and accessible and easy to digest than I’ve seen elsewhere; and I’ll be specific about what you actually need to do. The order in which you progress is important. You must learn to walk before you try to run. So, start at the start. And as I’ve said before: this system is designed to work, which means that it will require hard work, (like everything that’s worth anything). I wrote it for people who are fed up with being scattered and who also believe that heightened powers of concentration will get them more of what they want out of life. If this sounds like you: I can’t wait to help you solve this problem.

This number was revealed in studies conducted by Gloria Mark, PhD, on multitasking in 2022. It is a measure of the amount of time that study participants spend on a screen before switching to something else—either another screen or activity. In 2003, under the same study conditions, the average attention span was two and a half minutes. It dropped to 75 seconds in 2012, and now, in 2022 it is 47 seconds. In the most recent study the median length of time participants held their attention on one thing was 40 seconds; meaning half of all the observations were 40 seconds or less. The study has been replicated by several other researchers with substantially the same results.

One thing that has helped me get my focus back on track is employing an Enforcer. Basically I write a list of rules (simple stuff, no social media between X hours, focus on one thing at a time no matter what, time limits etc.) and then commit to stick to them for a week, or a month. The flashlight might want to jump around like crazy because I'm not well trained (weak, so weak!) but the Enforcer doesn't allow me to break the rules I have already agreed to.

It's exceptionally painful at the start, buy you just have to stick to the rules, stick to the rules, stick to the rules... Eventually the rules become easier to follow, and focus starts to become easier again.

Hi Matt, I've just recently stumbled across your substack. I loved this and your other articles on attention. Is the course you've mentioned for paid subscribers only or available somewhere else? I'd love to see what you've put together