Last year I wrote about a study which forced me to reconsider my relationship with pain. The upshot is that roughly 70% of men would rather painfully shock themselves than sit quietly in an empty room for a few minutes.1 We default to painful action over patient contemplation.

Before I read that study and wrote that essay, I was about to start an outdoor gear and apparel business. But through the process of writing I had come to see this business as a kind of ‘pain button’ — a way of shocking myself to feel and do something, a way of avoiding deeper questions about what I really wanted.

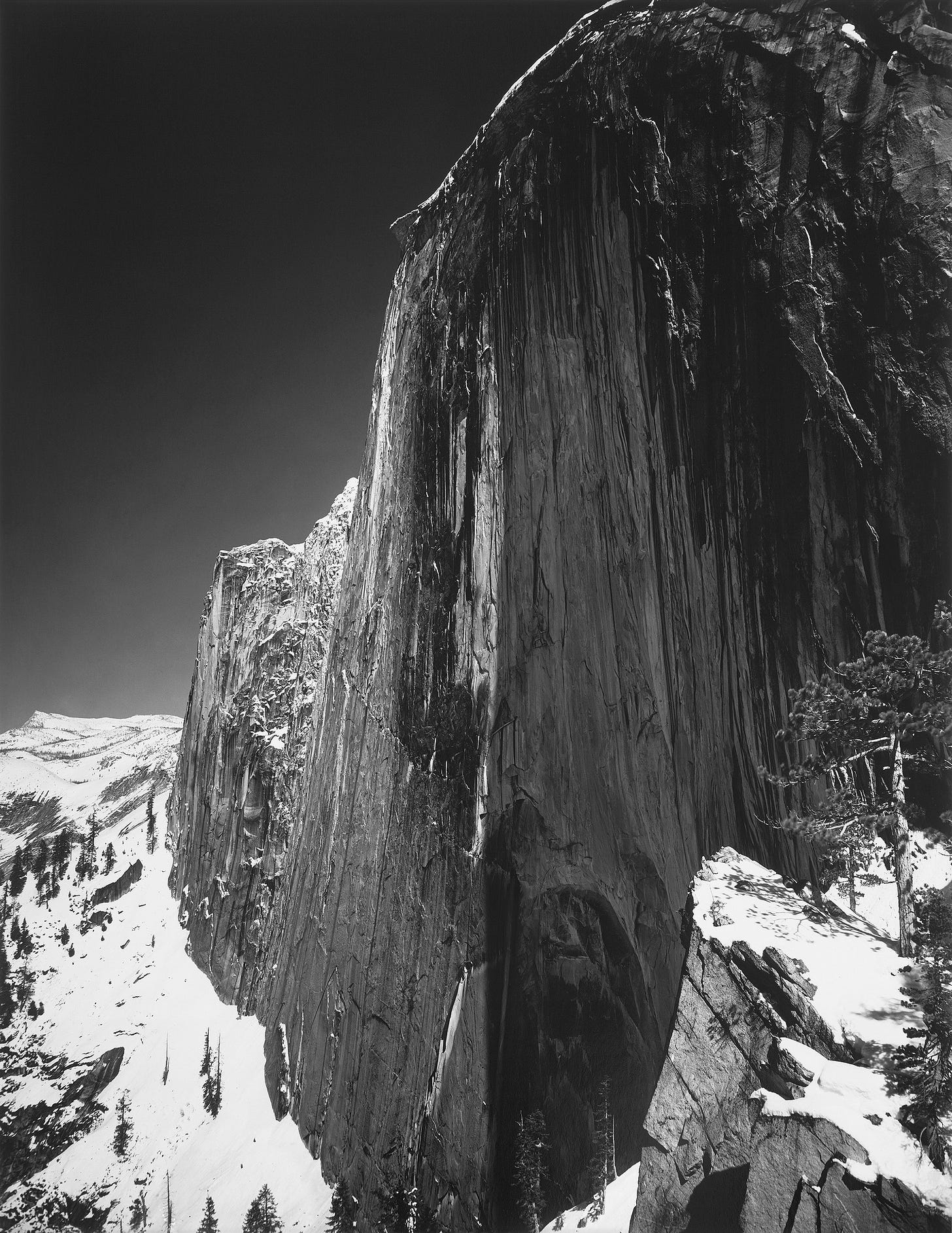

To people who were less familiar with the outdoor industry, I would describe the business that I was planning to start as the ‘next Patagonia.’ This was shorthand for ‘an outdoor company, but a serious one.’ Specifically, I was planning on starting an ultralight backpacking company. That was the business I slowly backed away from last year, and it is the same business I just officially incorporated. The products are in development, the brand identity is nearly finished, and every day I get a bit closer to launching it. It will be called Ansel.

In moving forward with the business, I knew I’d be answerable to my earlier writing. After all of the thought and introspection that went into writing an essay about self-inflicted wounds — was I really about to aim at my foot and fire? Or was it suddenly a good idea? What had I learned or done over the past six months that changed my mind?

There is a short answer and a long answer.

The short answer is that last November I began dreaming about the idea regularly, and for a whole week straight the dreams energized me so much that they would wake me at around 3 AM. Then, I would lie in bed for hours at a time because of some product idea, some minor brand detail, some marketing concept. Over a period of more than two years I simply couldn’t quit the idea. I tried every way I knew how: intellectualization, interrogation, public accountability, neglect, competition, jury trial. Finally, after so many backs and forths, I concluded that it would be more painful not to start the business, than to start it.

It was easy to imagine myself at age 80, sitting on a porch with my best years behind me, regretting that it was too late to build the thing I really wanted to build.

Fortunately, I’d given myself this out in my original essay:

“...the deeper you explore the purgatory of existential personal inquiry—the unknown—the better your chances of discovering the things that are worth suffering for. A family, a relationship, a business idea.”

Some things are worth suffering for. And after taking a long, hard look at myself, I decided this was one of those things.

But there is also the longer, more complicated answer. I spent a ridiculous amount of time trying to figure out how to figure out what to do with the rest of my life, and I figured it out. So I thought I’d share an abridged version of how this played out.

The Problem with Problem Selection

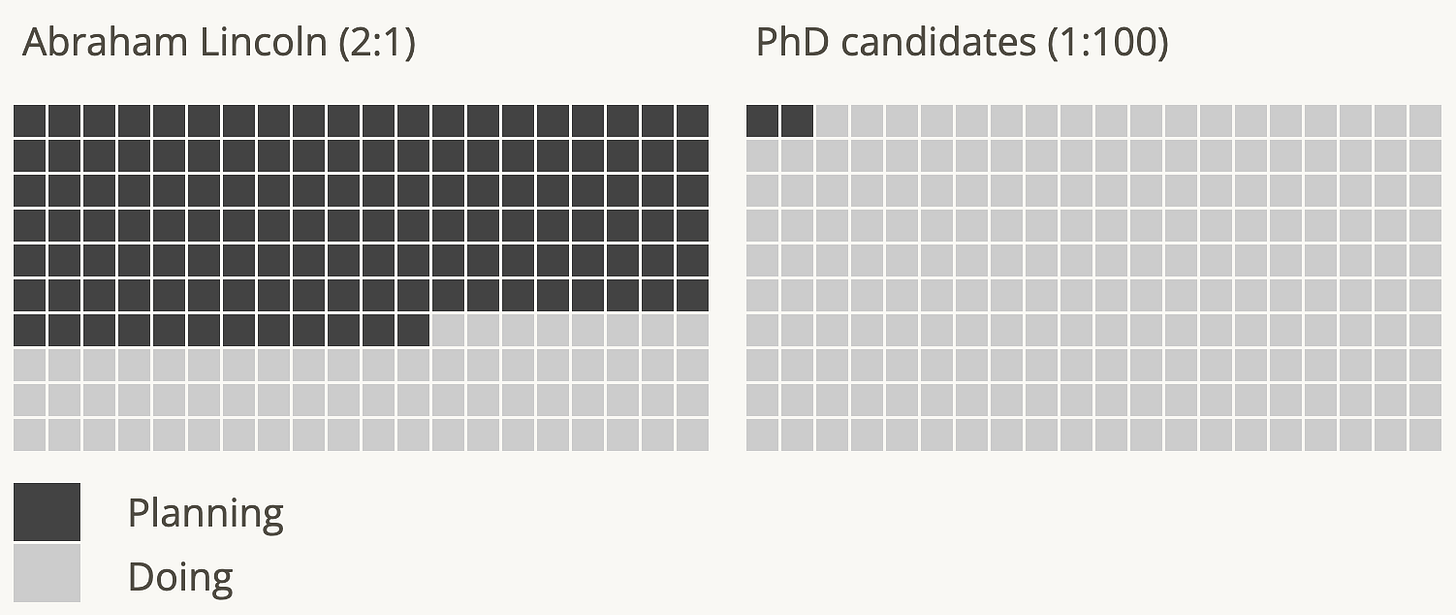

After writing The Pain Button I began to wonder how smart and successful people made decisions about the problems they chose to work on professionally. As I searched for answers, it became clear that there really weren’t answers. In fact, the most interesting thing I found was a Stanford research paper which revealed that PhD candidates spend 1-2 weeks deciding what they’ll spend 100-250 weeks researching. In other words: they spend one week planning for every two years they spend working. The conclusion of the paper was that very smart people are very bad at making decisions about what to work on.

Abraham Lincoln’s famous adage came to mind: “If I had six hours to chop down a tree, I'd spend four sharpening the axe.” His planning to doing ratio was 2:1. I became determined to develop a process that would lead me to a clear, rational answer — no matter how long it took. I couldn’t stand the thought of giving so much of my remaining life force over to the wrong thing.

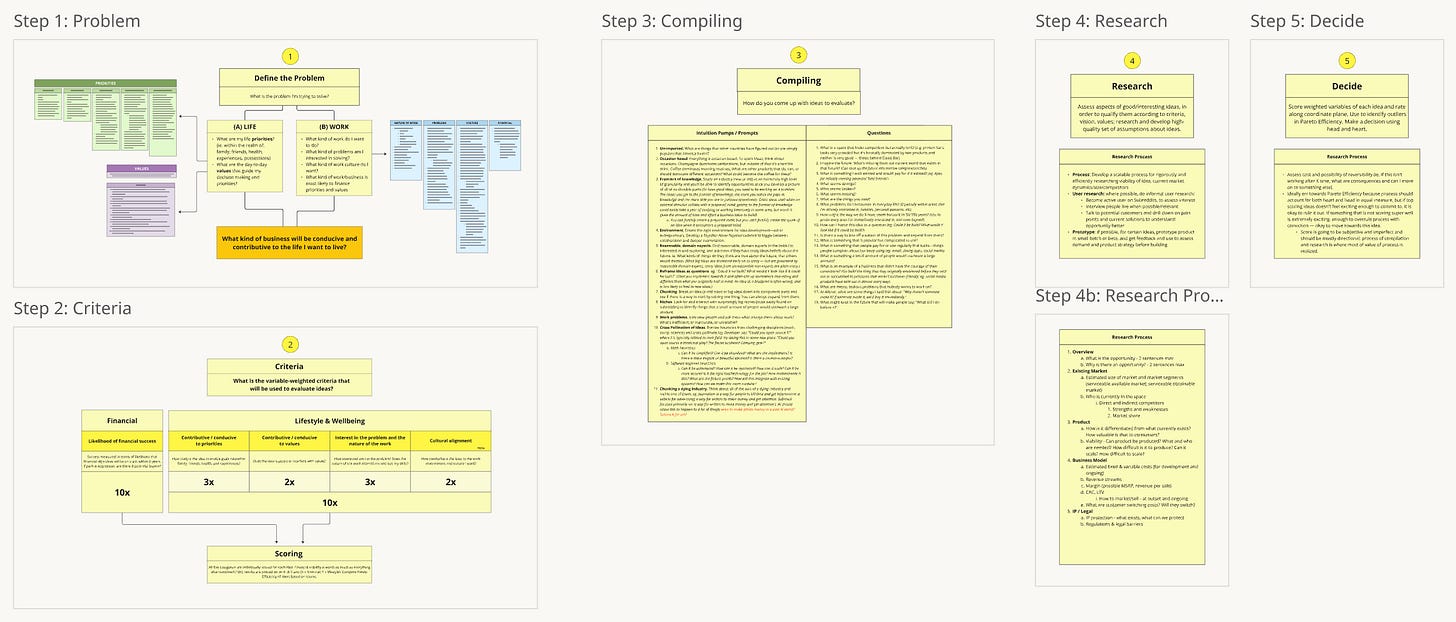

Eventually, I developed a five step process that I felt good about, and my process led to more than a hundred ideas that I spent time contemplating, researching, refining, and in some cases even soft-pitching to venture capitalists. But I would inevitably re-encounter the same problem: I would get an idea to ‘pencil’, then I would pause for just long enough to imagine what it might feel like to turn that idea into a company — a company that made fashionable air purifying respirators, or software that improved the employee reference process, or hardware that helped enforce school phone bans — and I just couldn’t imagine myself springing out of bed in the morning to work on it.

The ideas were failing some sort of autonomic passion-gut-check-test. So I moved ‘passion’ to the front of the process, and that short-circuited everything. I began generating ideas and shutting them down almost instantaneously. Something about passion and the cold rationality of the process were irreconcilable.

I went back to the drawing board.

Infinite Pain

As I considered where and why things were breaking down, I began to see my clinical process as an over-corrective response to the ‘Pain Button’ study. That is to say, I knew I had a high pain tolerance, so I was trying to avoid walking into a pain trap. I was looking for a business that would be the least painful to build and operate, and the most financially rewarding per unit of pain.

Meanwhile, as I was busy building my problem selection process, I was also devouring dozens of biographies about history’s greatest entrepreneurs. And I was beginning to recognize an incontrovertible pattern: entrepreneurship is pain and difficulty. There are no exceptions, there are only different ways of tricking yourself into enduring the pain.

While there may be a continuum of pain along the business idea spectrum, I came to see that anyone who believes that their fledgeling business concept will be pain-free is either inexperienced or delusional. In a startling amount of cases, if the entrepreneur knew beforehand exactly how hard things were going to be, they wouldn’t have started. The founder of Nvidia, which is currently the largest and most important company in the world, said exactly this:

I wouldn’t [have started Nvidia]. Building a company and building Nvidia turned out to be a million times harder than any of us expected it to be. And at that time, if we realized the pain and suffering and just how vulnerable you’re going to feel and the challenges you’re going to endure and the embarrassment and the shame and the list of all of the things that go wrong… I don’t think anybody would start a company. Nobody in their right mind would do it… I think it’s too much. It is just too much.

I encountered some version of this sentiment so many times that it seemed crazy not to pay attention. It also felt like something I could have said myself about my previous business experience.

The only option for avoiding the pain involved in building a company was to walk away from the game. But it is the game I have long felt born to play, and my compulsion to play has always felt deeply intrinsic. So I started thinking about the games within the game. Even if the pain was inevitable, surely there was an ideal way to pick the right problem to solve?

Everything (in my life) clicked into place when I encountered the concept of ‘infinite games.’

Infinite games are games played for the purpose of continuing to play. Finite games, on the other hand, are played for the purpose of winning (chess, soccer, war). This concept and dichotomy was laid out by James P. Carse, in his 1986 book about ‘life as play and possibility.’ It resonated profoundly with what I believe to be true about daily-meaning making — about life as play. But until now, the missing link in my life had always been an authentic sense of ‘professional play.’

Most people, especially hard-charging business-people, view work, parenting, hobbies, fitness, and relationships as finite games — as contests to be won — but when the game becomes the end itself, your objective is to keep playing for as long as possible. And when this is your objective, you become untethered to moving goal posts or external validation, and you get in touch with why you’re really playing in the first place. And why it’s fun to be a human. You become more creative, more resilient, and more fulfilled. You become a child. You can’t get enough.

If you’re interested, like me, in starting a consumer products business: you notice when infinite games are chartered into a business’s raison d’être — just as you can recognize the exact moment when they no longer are.2 The founders with product and brand legacies that impress me most are the ones who play infinite games.3 The privilege of creating great products, for them, is its own reward.

And the interesting thing is that when you play infinite games and you’re truly obsessed with what you get to work on everyday, you end up playing the game for a very long time, which means you invoke one of the most powerful forces in the world: the law of compounding. Your investment of time, energy, and attention, aren’t scattered, and over time, this non-diversified intensity ends up accumulating into something huge. You have more resources to do the thing you love the most — and you get to make it even better.

It turns out that the simplest heuristic for a ‘problem selection process’ is not five-parted, it’s not clinical, and it’s not particularly rational. It’s very simple: what wakes you up at night, in a good way? Would you want to work on that thing for the next 50 years, even if you knew it would be insanely painful and difficult?

If something comes immediately to mind, get started and don’t stop.

It’s actually even more crazy than this might make it seem: first, participants in the study were given a painful electric shock, then they were asked whether they’d pay to avoid being shocked again. Anyone who said they’d pay to avoid another shock was invited back. In the second stage of the study, participants were put in an empty room, alone, with no stimuli for fifteen minutes—no books, pens, paper, smartphones, nothing except a button that would administer the same painful electric shock as before. Before the fifteen minutes were up, 67% of the men pressed the pain button and shocked themselves

Interestingly, 25% of women shocked themselves. Still 25% too high, but so much lower.

Usually when PE takes majority ownership or when the founder dies or gets pushed out of their business

As I’ve studied great entrepreneurs, Walt Disney has become my favorite model for this. I’ve read every biography written about the man, and I’ve been rewarded in each new book with scores of obscure vignettes which illustrate what it looks like to play an infinite game. The great Italian craftsmen-as-entrepreneurs also stand out: Brunello Cuccinelli, Enzo Ferrari, Leonardo Del Vecchio. You can tell someone is playing an infinite game if their lifestyle doesn’t change much when they become fabulously wealthy — and when they keep pressing bets on their one true love, rather than hedging or diversifying.

Go Ansel! To infinity and beyond!

You have a strong vision and even stronger passion - Never give up!