How to get (really) good at things

Developing mastery through Deliberate Practice

I. It All Comes Back

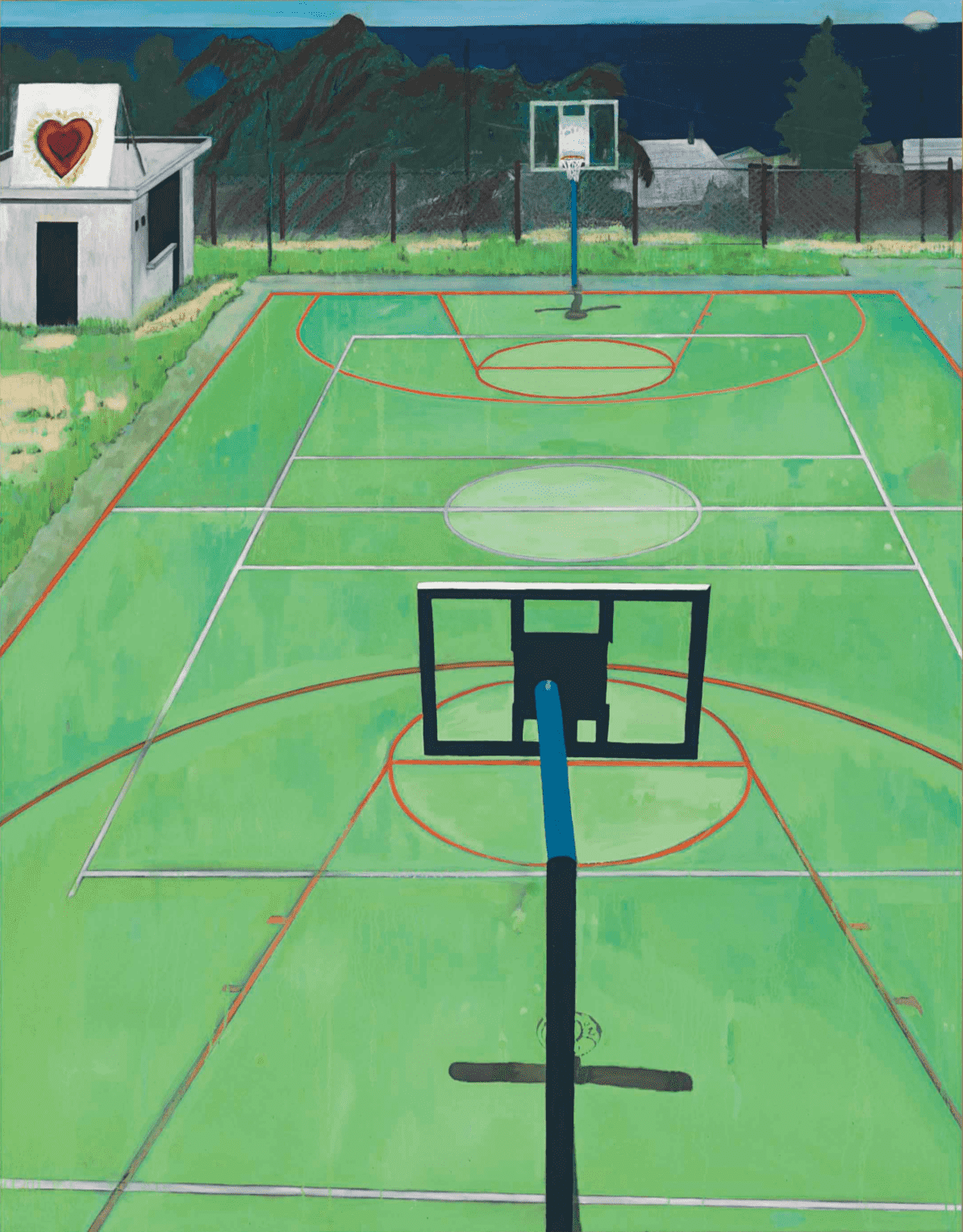

I’ve spent a full decade away from a basketball court and I’m standing at the free throw line now. My right foot squeaks into place on the sticky hardwood. I dribble twice, stare vacantly into the middle distance, look up to the rim, breathe out, shoot. Swish.

I shoot forty-nine more times. I count the shots, I count the makes. I make forty-four of fifty. Eighty-eight percent.1 “It’s like riding a bike,” an old coach once told me, as he made shot after shot in middle-age, with his beer gut and his bad knees, while I rebounded ball after ball. “You never lose it.”

And it’s true. You put in enough hours and it lives on inside you, even after ten years. Eighty-eight percent, after ten years.

I was simply letting my body remember. Tapping into a special knowledge of the hands, an embodied sense of physics and launch angles developed in an earlier chapter of my life. I was channeling something I’d obsessed over and mastered and made autonomic in high pressure situations. Something I could quite literally do, at one point in time, with my eyes closed.

II. Feel

When I was eleven years old, I entered the regional science fair with a logbook full of basketball drills that masqueraded as a science experiment. The project was called: “Does practice make perfect?” I’d shoot ten free throws and record how many I made, then I’d shoot one-hundred, then I’d shoot ten more and record how many I made the second time. Over the course of a few months, I observed and reported on the before and after delta. The project didn’t win any ribbons but I shot a lot of free throws, and I got good at shooting them.

This would turn out to be the first of many installments in a deliberate approach to practicing the special situations of basketball that I would employ over the next decade. I also made goggles out of throwaway glasses frames and duct tape, which blocked out the lower periphery and made it impossible to look down while I dribbled. I dribbled two and three balls at a time, juggling downward for an hour each day after school until my forearms were throbbing and my hands were black as tar from concrete and dust. I frequently dribbled basketballs that were two times larger than normal. This made the two and three ball dribbling drills diabolical. Eventually I combined many of these things while I weaved around cones at full speed. I attached rakes to trashcans and practiced dribbling around them, and shooting over them. In the summers, I often shot hoops until I could feel pain in my elbow joint. In your late teens it takes about six hours of continuous use to feel anything at all in the elbow joint.

When you add this all up, and much, much more, you develop something called feel. Across sports and across many disciplines you hear about feel. In basketball, feel is a flow state in the fingertips. Once it’s there, it lives in you forever.

Feel is acquired through a kind of pattern recognition that comes with decades of relentless repetition. In basketball, it manifests in the spatial awareness of bodies you cannot see on the court, based on the bodies you can see. And in the way your subconscious-self stretches out your hands to receive a bounce pass, so that your fingers lock perfectly into the ball’s black grooves.

It’s very comforting to have feel at something. It’s like seeing your best childhood friend after months or years or decades — there’s a warm familiarity to it. It all comes back effortlessly. Some people have feel with a piano, while carving on skis, while speaking a language they learned as a child. You’re out of your head. And that’s an increasingly rare and comforting place to be. It’s comforting, even if you rarely do it anymore.

Occasionally, I shoot free throws now — purely for catharsis, like a moving meditation. I’ve sometimes wondered, as I shoot, whether I’ll ever develop feel like this in anything else again. Whether that ship has sailed, and whether basketball — useless as it is to me now — is the only place I’ll ever have feel. At first, I thought so. Now I don’t think so.

Now I know the secret to feel, and it’s not exactly 10,000 hours. But it’s closely related. The secret to feel is something I’d been doing unknowingly throughout my basketball career: deliberate practice.

III. Deliberate Practice

Last year, I discovered the concept of deliberate practice circuitously.

I was reading “Flow” by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, and his concept of the ‘flow state’ turned out to be synonymous with ‘feel’ in contexts like basketball. Flow is embodied concentration, a loss of time awareness, a loss of self-consciousness — a full mind-body connectedness.2 But the leading scholarship on flow stopped short of making tactical suggestions about how to reliably cultivate feel and access it at-will.

I’d only ever felt serious flow states on a basketball court, and I wanted to know why, because I wanted more of it in other contexts.

In the subjects who experienced flow, there was a recurring element of intense, autotelic effort and ambition — while playing piano, rock climbing, painting, writing code, performing surgery. This pattern of peak performance led me to the research of Anders Ericsson.

In 1993, Ericsson published a paper that contained a concept that would eventually be oversimplified and ubiquitous: he observed that elite violinists accumulated around 10,000 hours of deliberate practice by age 20. Malcom Gladwell codified this into the “10,000 Hour Rule” in his book Outliers, and used it to explain the one weird trick that history’s famous elite performers had used to achieve mastery.

But Ericsson’s real point had very little to do with the number of practice hours, and everything to do with the ferocious intensity and very specific characteristics of those practice hours. 10,000 hours was merely an observation, plus or minus. In an effort to correct the record before he died Ericsson wrote a book that explained his real point: the concept of ‘deliberate practice.’ The book is called Peak.

IMHO, the ideas contained in Peak make it a true human treasure. It is a source of infinite leverage. The concepts outlined by Ericsson, unlike those shared by Gladwell, really do explain the outliers of the world. It is the consummate playbook for realizing one’s personal potential and even achieving world-class mastery.

Since reading it, I have applied the concepts at various scales — in focused 10-day sprints, towards lifetime skill mastery, and in my daily work.

Here is a compressed version of the seven cornerstones of deliberate practice, which eventually lead to mastery (though I, of course, urgently recommend reading the book).

Well-Defined, Specific Goals - each practice session focuses on improving a clearly defined skill or sub-skill; goals should be narrow, and measurable. (eg. for writing: ‘Practice writing 10 different opening lines for the same scene, focusing on immediacy, voice, and hook’ as opposed to ‘Write for an hour’)

Coaching - practice should be informed by expert coaching instruction. You must seek out new and capable coaches as skill level improves. Your coach should develop a training system that identifies: next stretch goal, optimal exercises to reach it, the sequence in which skills should be built.

Full Attention - must maintain conscious action and full engagement throughout practice period. If you're going through the motions (even with expert guidance) it isn't deliberate practice. Mental fatigue should occur. Sessions are often short and intense.

Immediate Feedback - you need feedback from capable coaches to understand what you're doing right and wrong, so that you can modify and correct effort. Over time you'll develop your own mental representations (which can be complemented by recording devices and other tools) to enable feedback via self-monitoring. Ericsson talks at length about the importance of developing and improving mental representations by studying the people who do the thing the best, deconstructing what they’re doing, and mapping it to your own practice.

Repetition and Refinement - skills are repeated often but not mindlessly. Each repetition incorporates adjustments based on feedback. The goal is not time spent — it is precision and improvement.

Gradual Increase in Challenge - you want to build to expertise in a linear progression, always at the edge of your comfort zone: hard enough to stretch you, not so hard that failure is inevitable. Build layer by layer upon the fundamentals, to let progress compound. You can't afford to go backward and relearn fundamentals.

Not enjoyable - since practice occurs at the edge of your comfort zone at a near maximal effort, it is usually not fun while it is happening. It is frustrating and intense. You must be motivated by a desire to improve, not by enjoyment or leisure in the moment.

If a person is willing to train and practice in this way, it almost always correlates with thousands of training hours. Whereas 10,000 hours spent in rote, naïve practice leads to a rapid and permanent plateau, 10,000 hours of deliberate practice makes true mastery possible.

IV. Practicing Deliberately

I practiced basketball deliberately for many years without knowing about the concept — almost always at the edge of my comfort zone, continuously finding that edge by dialing up different variables, employing regular feedback, forming mental representations by studying the greats. I spent several thousand hours of my childhood doing this.3

And this explains how I developed enough skill to play college basketball, as a comparatively small white guy with average athleticism. It also explains how I developed ‘feel’ over time, how I so often accessed flow in game-like situations, and how I can still make 88% of my free throws after not shooting a ball for ten years.

I originally became interested in deliberate practice because I hoped that it could help me develop that basketball-like feel in other areas of my life: while building a business, strength training, skiing, writing, mountain biking, learning a language, and developing other new skills.

Because it is so exhausting, I do think it should be selectively applied, but now that I’ve been integrating it, it feels a cheat code for skill development. It’s hard as hell, but it works. Here is a recent example:

How do you develop feel when you’re building a business? It’s not super straightforward because building a business is so many different things — and the progression of expertise isn’t as clear as it is with something like piano. But it’s the thing I spend the most time on, so I’ve been determined to layer-in deliberate practice wherever possible.

In my experience, the thing to do is to jam the principles of deliberate practice into the ‘most important project’ at any given time. I spend at least four hours each day working on my ‘most important project’.

Right now the most important project is fundraising. At my last business, my ‘practice’ and approach to fundraising was naïve and rote, and my results were middling. I wasn’t particularly good at it, and I didn’t like it. That business made it very far, but eventually it ran out of money. I promised myself I would never let that happen again, and to honor that promise, I recognized that I’d have to become great at fundraising. So I began employing deliberate practice on a more compressed time scale.

Recently, after I put my pitch deck through several rounds of critical feedback, I developed a 10-day sprint for mastering the pitch. I started by breaking the deck up into three sections (four slides each), and I spent an hour on each of the twelve slides over the course of three days, mastering and refining the pitch in manageable chunks.

Then I began pitching the whole thing together, first with notes, then without notes.

Once I mastered the whole thing, I compressed the pitch time from 28 minutes to 13 minutes. Then I began setting an alarm to go off at random times as I pitched. Then I searched for the most annoying and distracting podcast I could find, and played it at full volume while I pitched.4 Then I combined the random alarms and the podcast. Then I practiced visualizing the slides while making the pitch with my eyes closed. Then I pitched a few peers and gathered feedback and made adjustments. Then I made several versions of the deck where I randomized the slide order, and began pitching it out of sequence, with the heavy metal and an extremely annoying podcast playing simultaneously in the background. As a final test, I practiced the pitch with a MrBeast video playing on my screen, instead of slide deck.5

Each time I practiced the pitch, I wasn’t merely focused on maintaining composure and clarity through the mounting chaos — I also had a goal related to a specific aspect of my delivery: my body-language, vocal contrast and variety, intentional pauses, and facial expressions.

My head literally hurt after each daily session. I didn’t enjoy a single minute of it. But I recorded a pitch at the end of each day, and I did enjoy seeing the difference that ten days of deliberate practice made. It was astonishing.

In ten short days, I developed something resembling feel within a very limited scope. I’m excited to see whether ten, twenty, and thirty years of deliberate practice can transform something that is currently a vision in my head, into an iconic, global brand that makes the best outdoor products in the world. I believe it’s possible and even inevitable, and when it starts to happen I bet it will feel like stepping up to the free throw line.

For perspective: the best free-throw shooter in NBA history, Steph Curry, has a 91% career free-throw shooting percentage. Of course, this is in high-stakes game situations with large crowds.

This passage from “Flow” is so incredible. It provides some examples of what ‘feel’ and ‘flow’ look like in an anthropological context and modern ones.

“Eskimo hunters are trained to discriminate between dozens of types of snow, and are always aware of the direction and speed of the wind. Traditional Melanesian sailors can be taken blindfolded to any point of the ocean within a radius of several hundred miles from their island home and, if allowed to float for a few minutes in the sea, are able to recognize the spot by the feel of the currents on their bodies. A musician structures her attention so as to focus on nuances of sound that ordinary people are not aware of, a stockbroker focuses on tiny changes in the market that others do not register, a good clinical diagnostician has an uncanny eye for symptoms—because they have trained their attention to process signals that otherwise would pass unnoticed.”

Had I truly internalized and understood the principles of deliberate practice I would have employed them to a much greater and more organized extent, and I would have been significantly better.

IMPAULSIVE with Logan Paul

An extremely useful application I’ve found for AI has been in generating structured “deliberate practice” training, for specific objectives. The scaffolding of this training plan was derived from a lot of prompt engineering. Ultimately, it did require a considerable amount of human finessing, and ongoing adjustments to the plan as I was progressing, but ChatGPT was super helpful for building a initial skeleton.

loved this piece! surprised it doesn't have 1k likes at least

This is just so good, loved reading this. I too spent many thousands of hours of my childhood doing the same deliberate practice. I then didn’t with golf in my early 20’s and became a scratch golfer in about 2 years of daily practice (I golfed a lot growing up and was a 8-9 handicap prior).