Licking Honey from a Razor’s Edge

To become a mother and lose a mother

A few weeks ago my wife, Antra, put her father on speakerphone as we were getting into bed. Her father is a stoic man. He had called twice and now his voice wasn’t exactly steady. A few days earlier, Antra’s mother, Ilze, had seen a doctor about a migraine, and in the tests that followed they traced the migraine to a cancerous growth near her gallbladder.

After a week in the hospital — after half a dozen additional tests and the coordinated assessment of seven specialists — a veteran doctor sat beside her hospital bed and he cried as he shared the diagnosis. She had an unlocatable, untreatable, and aggressively metastatic cancer growing in her stomach. His prognosis: 6 months at most, with a generic chemo.

A week earlier — a day before the migraines — Ilze had gone for a long bike ride before packing her bags for a trip to America. She’d planned an extended visit to care for my wife and our soon-to-arrive baby, and she packed gifts, toys, and clothes that she had been collecting for years, for this moment. The due date was in four weeks. And now she was in the inpatient ward in the Australian capital, wondering if she’d live to hold her first grandchild.

Two days after the prognosis, Antra and I flew to Australia for the indefinite future. We left on the longest day of summer, and we were greeted forebodingly by the winter solstice. Within an hour of our arrival at the hospital the head oncologist visited and shared that he no longer recommended chemo given the rate of metastasis and the ‘tempo’ of advancing symptoms. He did not cry, but he seemed to find it very difficult to say what he had come to say, and so there were times when we had to ask him to speak more plainly. In the end, what he said was that Ilze had ‘short weeks’ to live — and that there was a low probability of her meeting our child.

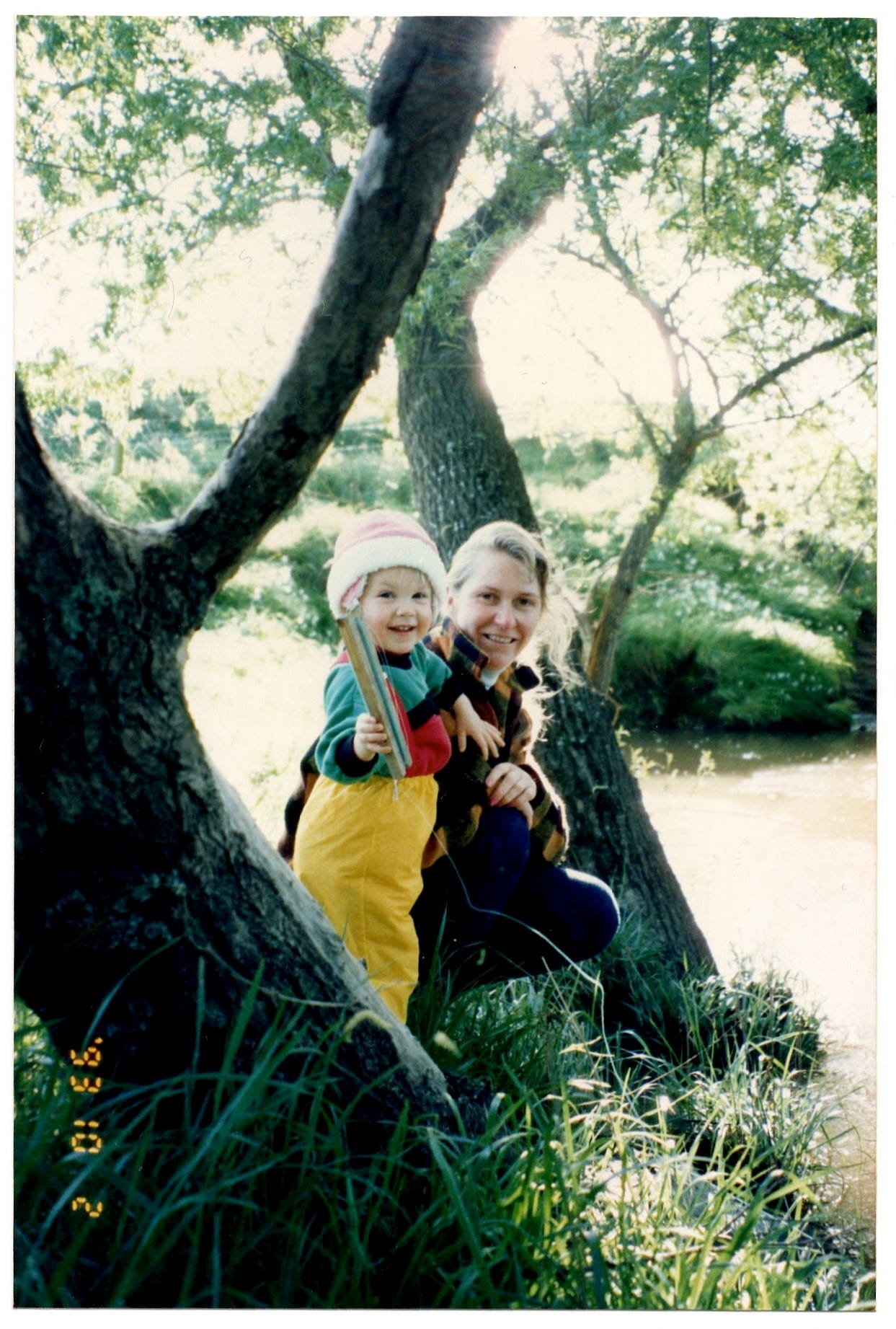

I’ve now spent a few weeks at the foot of my mother-in-law’s deathbed, and I’ve watched my pregnant wife become a mother to her mother. I’ve watched her nurture, cook for, spoon feed, massage, serenade, cuddle, shower, and love her mother beyond belief, from dawn until dusk. The daily vignettes are unimaginably beautiful and painful, so raw and gut-wrenchingly poetic that they split you right open. My wife, the daughter, grows life in her womb, a life-force that kicks so powerfully that it is often visible from across the room — while her mother’s body grows the thing that will bring death. The two paths moving involuntarily, seem increasingly destined to miss each other.

Our days here are slow. Much too slow to count for anything in today’s world — but unlike some entire years, each day here is marked by quiet, life-altering moments of introspection, reflection, and conversation. As life and death march inexorably forward, there is no question about what lays ahead for us, and so we speak openly about it and we compress a year’s worth of storytelling and vulnerability and gratitude into a few waking hours. We open the safe and hear the story of Babuņa’s mink shawl and her amethyst jewelry set — smuggled out of Latvia on the eve of Soviet occupation. We hear about the magic rock that fell through the sun roof in the Outback, and the wonky clay horse whistle in the kitchen. We learn about the history and utility of Baltic amber — the 44-million-year-old, fossilized tree resin, prized for its purity — and we pick through an incomparable collection of amber relics.

We discover what it means to be connected to something deeply ancestral: we document a family history, and absorb a compressed postdoc in Latvian symbology, jewelry, and culture. Ilze has been described as the ‘guardian’ of Latvian traditions, rituals, and knowledge — a virtuosic silversmith, an award-winning teacher, a cultural historian. With every new revelation we mourn what we’re losing, and we scramble to preserve what we can — making voice memos, filling notepads.

It’s an unspeakably sad and tragic paradox — to watch someone you love become a mother and lose a mother within a matter of days. It’s a duality nobody deserves to face. Between breaks in caretaking and conversation, a deep cosmic unfairness sets in. Especially as the pain, fatigue, and nausea advance. The only way I can make it make sense is to find the beauty in all of it. As difficult as the situation is — and perhaps because of how difficult it is — the beauty is always close at hand.

Something beautiful happens when the end of something you love looms in the periphery. When there is an imminence and inevitability about it. When the end is ‘short weeks’ and not years away. The days don’t feel longer, but each day and each moment feels precious and sacred in a way I’ve never known before. Given even a few weeks' notice, the death of something or someone special becomes a prism for so much of what matters and has mattered in a life. All that was original and irreplaceable and sublime in a person — you see it with astonishing clarity and you absorb its final essence. An urgent intentionality envelops you, and preserves memories and moments like the ghosts of history frozen in amber.

Beautifully written words and a deeply touching message behind them. So much love to you all. ❤️

Such beautiful words, Matt