From the Mother

On death and life, and the stories in the sadness

My wife, Antra, is at her mother’s bedside, exactly forty weeks pregnant, listening to her mother’s favorite music, holding her mother’s hand, sobbing in the fetal position, while her mother draws her final breaths.

I bristle later, when the nurse says “everything happens for a reason.” I haven’t worked out the reason just yet, haven’t found the narrative order in the tragic timing — still haven’t found the right metaphors.

A reassuring story can’t arrange a meeting between my late mother-in-law and my unborn child, but I keep searching for one anyway. It’s like Joan Didion said, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

And sure enough, the metaphors do emerge. And so do the stories.

Around midday on August 3, the clouds burn off. The swell picks up. The birdsong stops for a moment of brief commemoration. The sea shell looks like the sun.

My wife tells me about a conversation she had just before we flew to Australia. She is leaving yoga class the morning before our flight, and a wise-looking, older woman she has never seen before stops her at the door and asks how she is feeling in her pregnancy. Antra falls to pieces and shares that she has just learned that her mother in Australia has received a terminal cancer diagnosis.

The woman puts her hand on my wife’s shoulder, and without pausing she looks her dead in the eyes and says, “Your mother needs you. Your baby needs you. You can do this. Life doesn’t give us more than we can handle.”

I’ve heard my wife share this story five times now.

I

The baby is due tomorrow, it’s midnight and labor has just begun.

Except, it hasn’t.

Prodromal labor has begun. Braxton-Hicks contractions have begun. Part of the real thing, but not determinative. It could still be another week. Or two. My wife promised herself she wouldn’t fall for this. But she just did.

She falls for it because she needs labor to begin. Because if this really is labor, her mother will meet her baby. And if it’s not, she won’t. And two days ago the palliative care doctor did say: “Your mother willed herself beyond her prognosis to meet that baby. I have a strong feeling she’ll make it.”

But it’s not labor.

II

The visiting nurse makes her morning observations, then she meets us in the kitchen. She shares that Ilze has entered the ‘active dying’ stage.

We all knew this was coming. We’ve had a month to prepare for this. Only, nothing can prepare you for this. For the irregular breathing, the occasional gasps, the groans, the involuntary jolts, the hollow temples, the sunken cheeks, the eyes rolled back. It feels so unfair. It is so unfair.

I play it forward: in a few hours my wife won’t have a mother. My children will never meet the person who created their mother, who made their mother so special. Will never know the woman who picked out their first teddy bears and loved them to bits before they were even conceived. I sit beside the bed and I’m stuck in a loop of parallel realities. It feels related to denial. I think: Is it possible that this isn’t actually happening? Couldn’t she just as easily live for another 30 years? She could teach my kids so much. She could still look like she looks in this photograph. Or that photograph from six weeks ago. Healthy, full of life. Surely this is some sort of glitch? Maybe we’re really back in Oregon right now and this is some awful dream? Maybe she’s in Oregon with us, preparing postpartum meals for my wife. Biking along the river at sunset.

My mind keeps playing this trick on me — sometimes it happens in a flash, sometimes it’s drawn out, sometimes I dream it. A day passes in this fugue state. I do another loop and it’s interrupted by a gasp. And I’m back here, and it’s over, and she’s gone.

III

Australian Aboriginals have a belief, I’m told, that when you travel by plane or by car, your soul takes time to catch up with your body because the soul can only move at a walking pace. This causes ‘soul lag.’

I arrived in Australia by plane a month ago from America. Maybe there really is a sundering, because nothing makes sense right now. Perhaps my soul is still traveling somewhere in the Pacific, leaving my mind and body to sort out the essential facts of the current situation.

The facts are these: I’m very far from home, my wife is overdue with our first child, and her mother is dead.

IV

“Don’t kink the hose,” Antra says. “Don’t suppress the feeling. Let the feeling pass through you. The only way out is through.”

She tells me these things. But I’m not about to birth a human. Not the one whose beloved mother is being cremated tomorrow.

How could someone be subjected to this? And how could someone handle this sort of thing with grace, with strength, with poise and eloquence? Without a hint of self-pity?

I’m not sure how. But somehow Antra knows.

Maybe she learned it from her mother.

V

Four days after Ilze has passed away, the cremation and memorial service is scheduled for eleven in the morning on August 7th.

As arrangements are being made, my wife’s father turns to me and says: “I reckon the baby will come on the seventh. We’ll have to cancel the service.”

On August 7th the real contractions begin. The service is cancelled. An hour before the service is scheduled, the baby arrives.

Later I ask him how he knew about the seventh.

“I just had a strong feeling,” he says. “Ilze was waiting for the baby. The baby had to come before the cremation.”

VI

A few weeks ago, some of Antra’s closest friends from different parts of the world organized a mother’s blessing to usher in her motherhood. The ceremony was planned before her mother became sick, and now it has assumed a special poignancy because Antra is zooming in from an oncology ward in Australia, being celebrated for her impending motherhood alongside her own dying mother.

As the ritual unfolds, a yellow, beeswax pillar candle burns beside each of the women and the ceremony concludes with a mantra-like song:

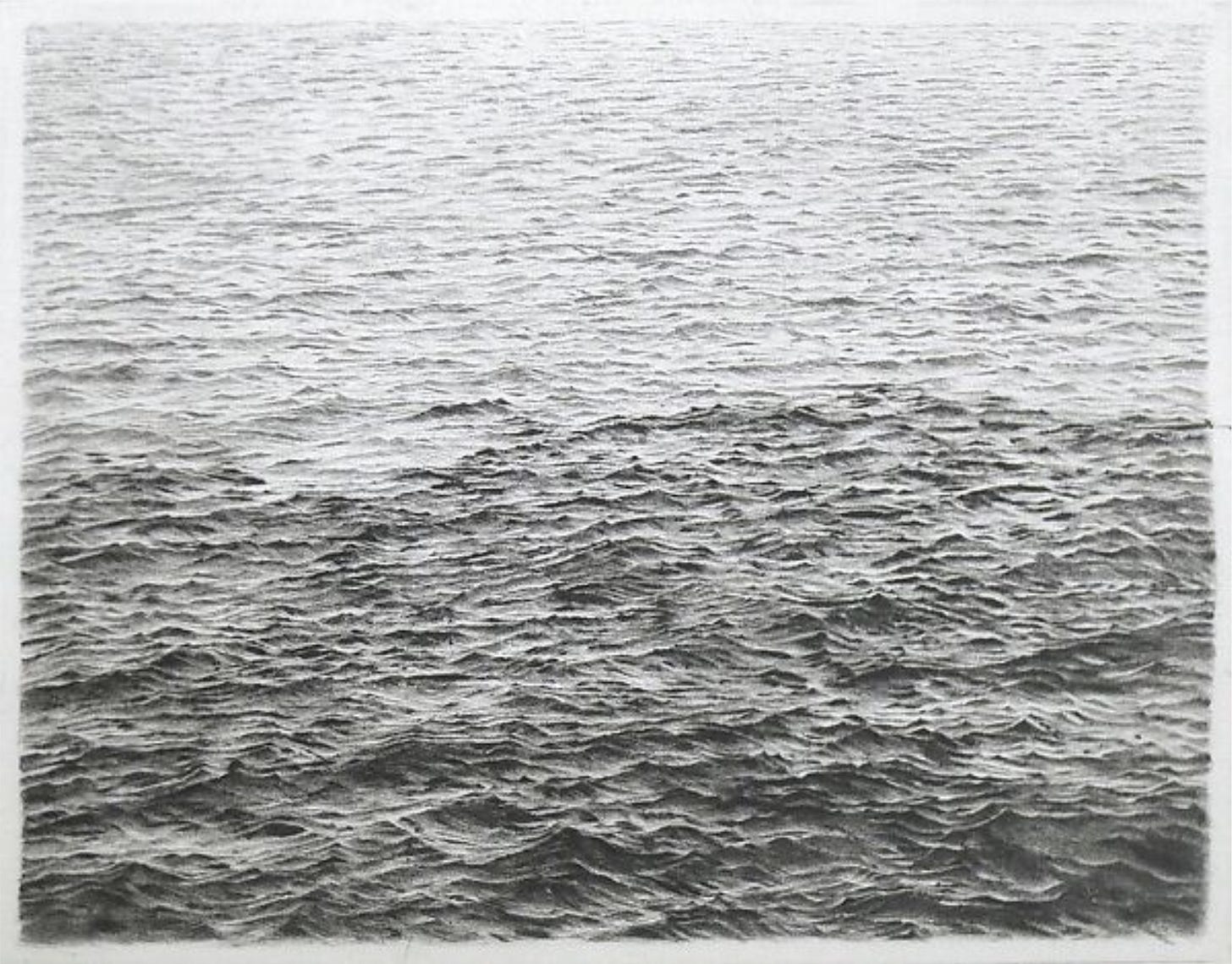

We all come from the mother, and to her we shall return, like a drop of rain, flowing to the ocean

Antra and her mother find comfort and connectedness in the cyclicality of these words. It commemorates Ilze’s profound, lifelong connection with the ocean. In her final days, Ilze and Antra draw strength from the message and they sing it together. And when Ilze passes away and the mortician comes to collect her body, Antra and I visit the ocean.

When we arrive, we’re greeted by a huge swell and a rising tide. The waves form further out toward the horizon than in the days before. They roll in ceaselessly, rise higher, fall heavier. The waves thunder down relentlessly — crashing into a mercurial mist, which glows silver on the pastel twilight.

We walk along the shore and Antra asks me to find a shell for her mother. I find one and I show it to her.

“Yes. That’s the one,” she says, “It looks like the sun.”

“It does.”

I pick up another shell, similar in size and shape, and another smaller one. I say: “This one is for you. And this one is for the baby.” She smiles and nods and takes the shells.

She looks out into the ocean and she sings. Softly and self-consciously at first, then louder and louder over the booming waves, she sings until she can no longer sing from soreness and sadness.

We all come from the mother, and to her we shall return, like a drop of rain, flowing to the ocean

In the evening, I enter our bedroom after the sun has set. It’s dark out and the shades are drawn and the single source of light comes from an altar at the center of the room — the beeswax pillar candle from the mother’s blessing sits upon a coffee table, and below the candle lay three sea shells that look like the sun. Antra is kneeling before the candle and staring into the light and sobbing from the deepest, darkest place she has ever known. Candlelight flickers radiantly across her tear-soaked face. Her shirt is dripping wet from crying.

She gasps. I wipe her face dry and all she can say is, “I’m just so sad.” I calm her and hold her and we go to sleep.

On the second night after her mother’s death, it’s the same.

On the third night it’s the same too, except I wake a few hours later to the strike and sizzle of a match — to the beginning of a different kind of ceremony.

It’s morning but it’s dark and it will be dark for many more hours. Antra lights the candle, re-aligns the seashells with her middle finger, kneels and breathes deeply. Her eyes are closed and she isn’t crying. She breathes with ritualistic serenity.

She shudders and shivers. I look over from the bed. There are goosebumps on her arms. I walk over to her and put a blanket over her shoulders and I put my hand on her back and a wave of contractions ripples through her body. Then it’s over and she breathes again.

Five minutes of focused calm, one minute of rippling. Four minutes off, one minute on. Three minutes, one minute, three, one, three, one.

The contractions intensify. She sits in front of her candle and her shells, she breathes, groans, breathes.

The contractions intensify. The contractions roll in from the horizon like waves, rising high, falling heavy, falling heavier. Rolling rhythmically and ceaselessly for hours. Waves, thundering down relentlessly, finally erupting into an unimaginably savage and sublime thing.

I steady my shaking hands under a tiny human head and then another primal push and then I’m holding a whole baby body. A baby boy.

The pillar candle casts a warm, reassuring glow onto the boy as he searches for air. He finds it, he gasps.

I hand Antra the child and she brings him to her chest. She is stunned by a warmth and joy unlike any she has ever known, she turns to the boy breathlessly and says, “My god. It’s Emil.”

The circle closes. The blinds are raised, the candle is snuffed.

We all come from the mother, and to her we shall return, like a drop of rain, flowing to the ocean.

This is gorgeous. Thinking about you and your family so much

Beautiful tribute Matt. Sending love and prayers to your family ♥️AK